It was a sensible thing to do, after our forebears discovered that food could be summoned from the earth beneath their feet; rather than roam, they remained. And where they remained, they built shelter. As they settled down, they came to recognise their reliance on the vagaries of the weather; indeed there seemed to be something almost human-like in its caprices. And so great sacrifices were made to propitiate these vital but fearsome forces in the sky.

In outward appearance, houses are much evolved since the days of those sedentary pioneers, but the basic function is unchanged: to provide shelter from the elements. Well, almost unchanged. Advanced civilisation has managed to assign a second function to houses: wealth-generation. In some places, so powerful has this function become that an apotheosis of sorts has been realized for the once-humble abode, and we find ourselves appeasing this latter-day deity with all the enthusiasm of our trembling forebears.

No inquiry into the direction of Aussie interest rates would be close to complete without a look at the almighty housing sector, and the unique position it holds in the modern Australian economy.

So that’s what we have here.

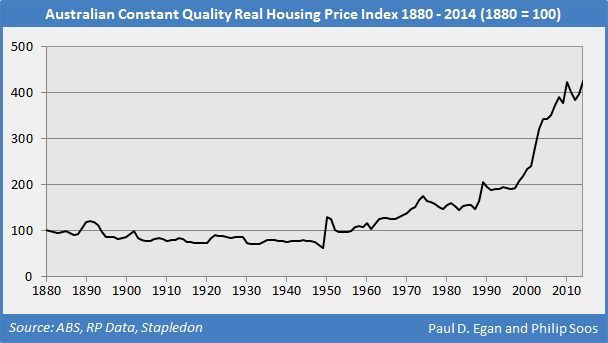

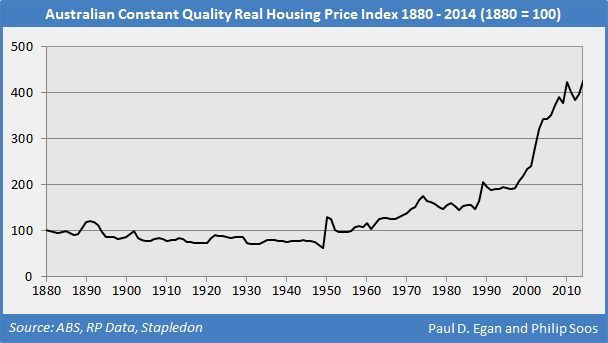

For the 60 years or so between the 1890s depression and the post-war reconstruction/Korean wool boom of the 1950s, Australian housing was a pretty lousy bet, as illustrated in this chart from Philip Soos and Paul D. Egan.

Even after the trend reversed with the post-war boom (see terms of trade chart for reference), house price growth through to the late 1990s largely tracked the long-term growth in per capita incomes. Then as the millennium approached, and despite plausible claims that confused computers would end civilization as we knew it, Australians learnt to stop worrying and love the abode.

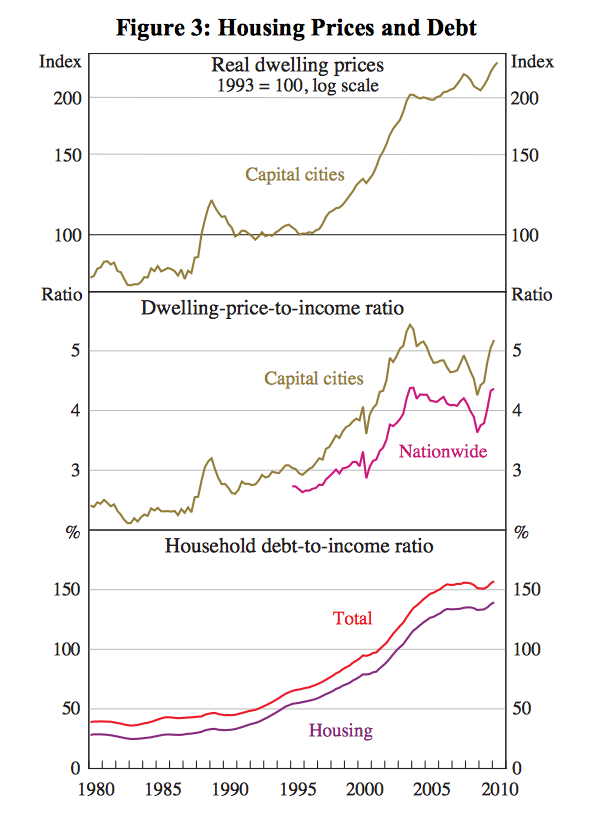

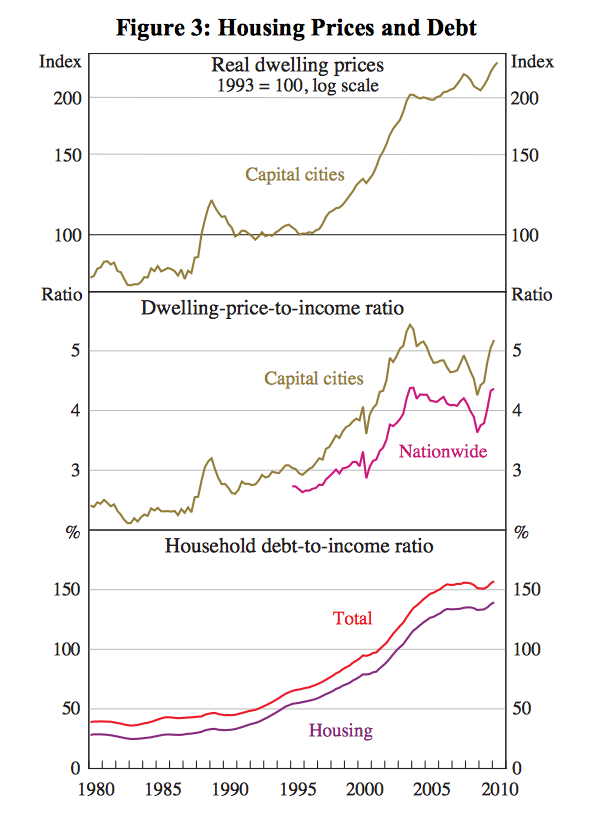

Between 1997 and 2003, dwelling prices in Australia doubled, rising by an average of 13% per annum, far in excess of income growth. This therefore drove up the ratio of house prices to incomes, with the additional demand arriving by a surge of household borrowing. (See Bloxham, Kent, Robson, 2010 and RBA, 2003b for detailed discussion of the Australian housing sector.)

There were a number of factors that propelled the housing market through this period, however the primary influence was a halving of interest rates over the decade to the late 1990s. Inflation stabilised at a low rate during the 1990s, after a sustained period of rapid, volatile increases in consumer prices. Lower inflation saw a decline in interest rates which made mortgages more accessible. Financial deregulation in the 1980s heightened competition amongst banks and other credit providers, which further reduced interest rates and increased the availability of credit to households.

If easier access to credit ignited the boom, then structural supply constraints, government incentives and good old ‘animal spirits’ acted as the kerosene. The favourable tax treatment of property investments became particularly incendiary. In Australia, tax losses incurred on an investment property may be offset against other taxable income (the ever-controvesial ‘negative gearing’), meaning that regular cash outlays incurred through an investment property can be far below the actual costs (including mortgage interest payments). This in itself isn’t necessarily an irresistible attraction, however combined the strong appreciation in house prices in the late 1990s, it proved a potent mix. Egged on by a metastasising property investment seminar industry, the era of the Australia housing investor had dawned.

Although the growth in the proportion of all mortgages going to investors moderated between 1997 and 2003, this was largely a result of a similarly enthusiastic dash for credit by owner-occupiers, and in fact the level of total investor mortgage credit in the economy exploded in the new millennium. The approximate period of this investor frenzy is highlighted on the following charts. (All data sourced from the ABS).

Consequently, growth in house prices greatly accelerated over this period. (The house price index chart combines two series which are not directly comparable, since there was a change in methodology after 2005. I’ve rebased the second series so that it matches up; it’s not precise but it’ll do for the purposes of illustration).

As you can see, 2002 and 2003 saw especially rapid price appreciation, and slowed markedly thereafter.

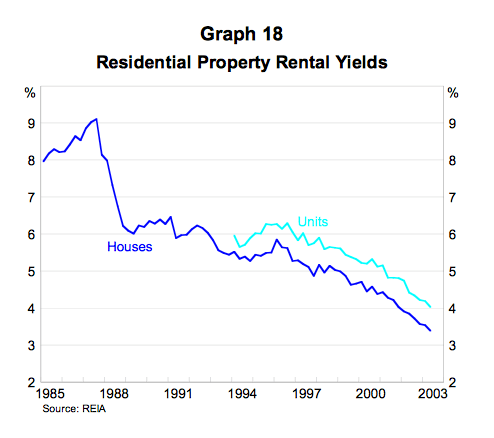

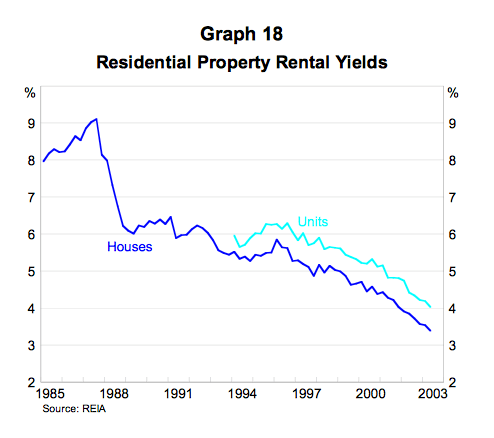

We’ve already seen that the boom pushed house prices to great heights relative to incomes. They were similarly expensive when valued by another key metric: rental yields.

I don’t find it much of a stretch to label this episode a ‘bubble’, with the single but important qualification that it did not burst with any severity.

Bubbles have long been confounding phenomena for the economics community. Under once-fashionable assumptions, there can be no bubbles, for they defy human rationality. And yet we humans possess a stubborn contempt for our theorised behaviour, and bubbles are most assuredly real. But how to spot them? A popular view holds that a bubble can only be identified by an autopsy; until it bursts, we cannot definitively say that this or that asset market is a bubble.

I do not subscribe to this view. Rather, I agree with the argument it is possible to identify bubbles before they burst, with some degree of confidence, through key valuation metrics. The more pronounced the departure from fundamental value, the more likely a market is to be experiencing a bubble. Of course, there is always uncertainty. In particular, identifying the signs of bubble does not tell you when or how it will burst, nor does it preclude the possibility of external circumstances changing in ways that shift the dynamics of the market.

On this, Australia provides an exceptional case in point. Conditions in the housing sector leading up to 2003-2004 were undeniably bubbly, and without a sudden and spectacular rise in national income, would almost certainly have entailed a nasty hangover. Fortunately, a sudden and spectacular rise in national income is exactly what we got, courtesy of the biggest terms of trade boom in our nation’s history, which happened to arrive in earnest almost precisely as we passed peak of the housing boom. Again, the approximate period of the most manic half of the boom is shaded.

This was extraordinary good fortune, even for the Lucky Country. Tax receipts pouring in from the corporate sector allowed the Howard government to reduce the tax impost on households. In addition, households came to regard savings as an unnecessary encumbrance, leading to a consumption boom. The surge in household income brought the value of house prices relative to incomes down to a more reasonable level. Anyone worrying about a housing bust following the boom was quickly disabused of the notion (the article links don’t seem to work on that page, but you get the picture).

This had important ramifications for Australia. It largely locked-in the price gains from the boom, further reinforcing the belief that house prices do not fall in a significant or sustained manner. In conjunction with the experience of the global financial crisis- when housing markets crashed around the world but Australia’s sailed through thanks to supportive government schemes, a second leg higher in the terms of trade, and a domestic investment boom- Australians now have a powerful historical precedent supporting the case for property investment (exemplified here by Adam Carr, with more than a trace of hubris).

Groundhog Boom

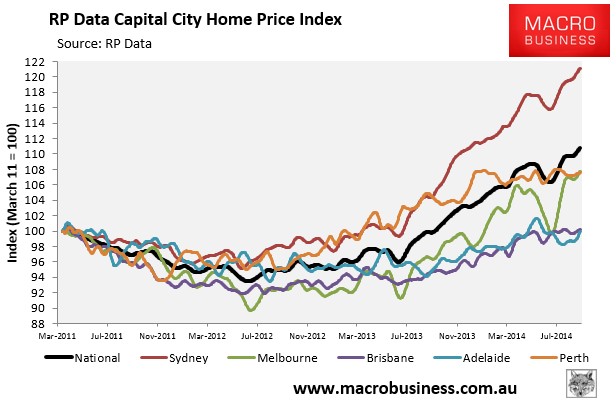

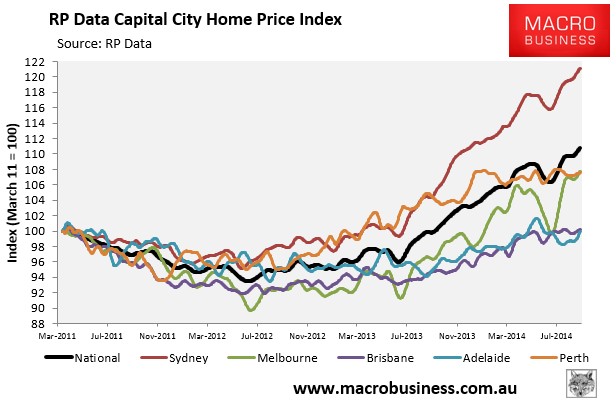

As is evident on the ‘housing finance commitments’ chart above, there has been a renewed surge in investor activity in the housing market in the last couple of years. The impetus for this was, as usual, a sharp decline in interest rates. As such, house prices have been buoyant, led by Sydney (as in the previous boom).

We can clearly observe the 2014 winter lull on that chart from MacroBusiness, which some commentators conjectured to be the peak. Now that house prices have picked up the pace again, we await to see what the spring buying season brings. Are we nearing the peak, or will we scale new heights over the next 12 months? Will the laggards follow Sydney into the stratosphere, or will Sydney be left lonely on the mountaintop?

They’re pertinent questions (at least to this series of posts!). The housing boom, Sydney-centric though it may be, is really all that’s preventing the RBA from cutting further, since the only sectors of the economy responding with any verve to lower interest rates have so far been house prices and residential construction. Households remain reluctant to open the purse strings, despite the fabled ‘wealth effect’ of high asset prices, and the non-mining corporate sector is for the most part loath to invest, even with cheap credit, which is hardly surprising given the terribly elevated cost structure bequeathed to the economy by the terms of trade boom.

If house prices can find the legs for another big move higher, don’t expect the RBA to cut interest rates. As Glenn Stevens has articulated, there is concern within the bank about the state of housing. Conversely, if house prices steady and then start to cool, there is little else in the economy indicating a case for higher interest rates. Speculating on the precise path of house prices is more art than science, and depends on how long investors remain bullish on a market in which end-user demand is increasingly scarce.

One thing is abundantly clear, however; and that’s the radically different outlook for the terms of trade this time around. We are witnessing a robust, if localised, boom in the housing sector, with a high level of participation by buyers who are simply looking for capital appreciation. If a ‘once-in-a-century’ export boom rescued property the last time around we saw a speculative boom, then the question property bulls must answer today is, what will rescue it this time? (Admittedly, the boom was of a greater magnitude in 2003, though the current one started from a higher base.)

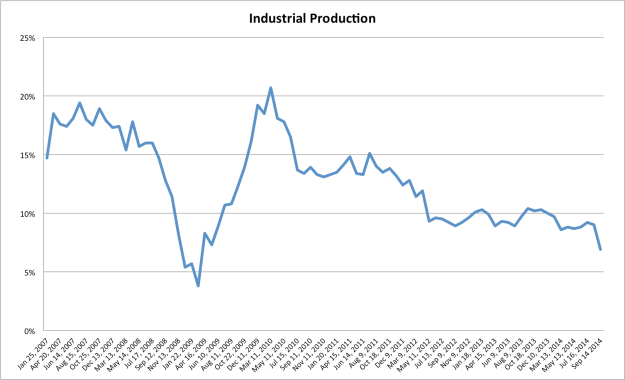

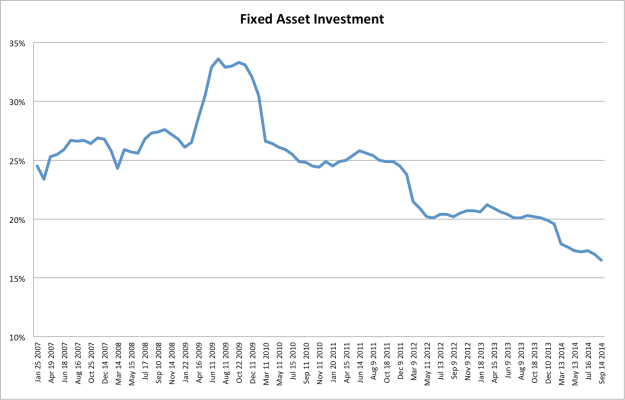

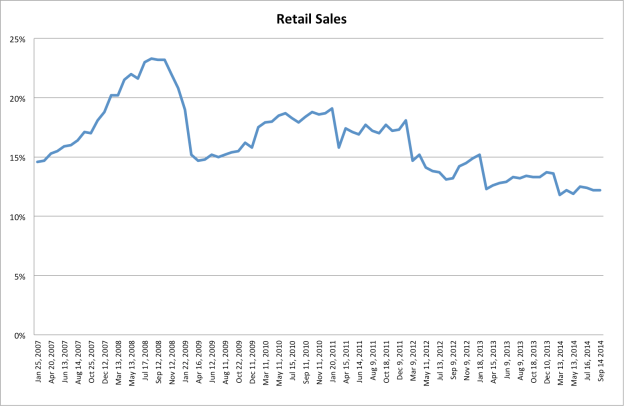

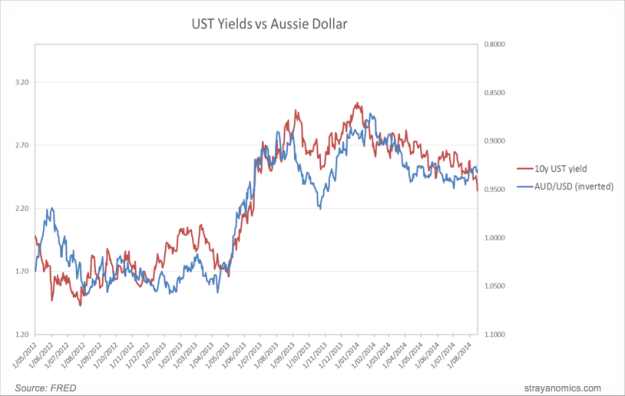

In stark contrast to the pinnacle of the last boom, national disposable income is now in decline and will continue to decline until either our terms of trade rebound or our real exchange rate falls far enough that improved competitiveness puts a floor under disposable incomes, at a much lower level. I outlined in the previous post why we’re unlikely to see China drive the terms of trade higher again. It’s not impossible in the short-run, but over the medium- to long-term, the glory days are well and truly past.

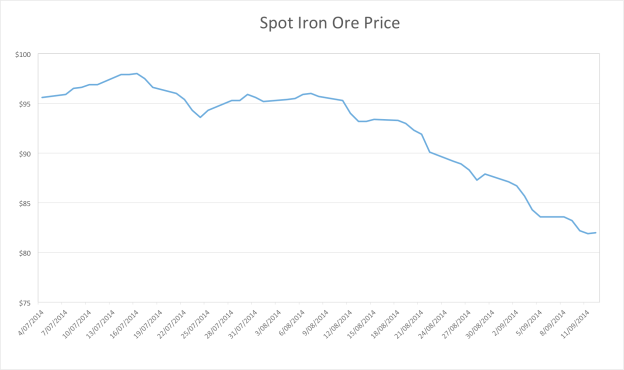

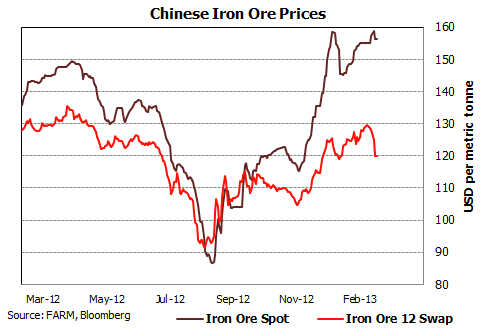

Recall that the overwhelming consensus in Australia is that the RBA will hike in its next cash rate move. The expectations underpinning this view are that the terms of trade will stabilise, with iron ore rebounding to roughly $100 a tonne in the near future, and that the interest rate-sensitive sectors of the economy go on expanding, until household consumption and rising asset prices start to tighten the labour market and pressure consumer prices, such that the RBA must lift interest rates.

This is not my view however, and I’ll wrap up this series in the next post with a summary of why that’s the case.

Part 5: The End of the Beginning