The RBA released its biannual Financial Stability Review yesterday, offering the usual trove of insight to anyone interested in such troves.

One big takeaway is that the central bank is now unambiguously acknowledging the dangers emanating from the housing market (which I’ve covered in the series on interest rates):

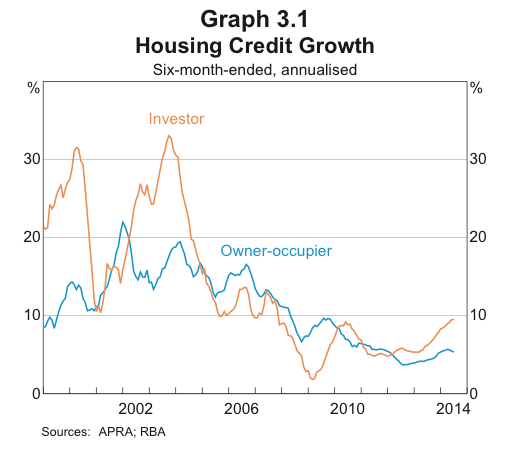

The low interest rate environment and, more recently, strong price competition among lenders have translated into a strong pick-up in growth in lending for investor housing – noticeably more so than for owner-occupier housing or businesses. Recent housing price growth seems to have encouraged further investor activity. As a result, the composition of housing and mortgage markets is becoming unbalanced, with new lending to investors being out of proportion to rental housing’s share of the housing stock.

If we jump to the Australian Financial System section, the RBA had the following to say:

Australian banks are benefiting from improved wholesale funding conditions globally and, in turn, an easing in overall deposit market competition. Lower funding costs are facilitating strong price competition in housing and commercial property lending. Fast growth in property prices and investor activity has increased property-related risks to the macroeconomy. It is important for macroeconomic and financial stability that banks set their risk appetite and lending standards at least in line with current best practice, and take into account system-wide risks in property markets in their lending decisions. Over the past year APRA has increased the intensity of its supervision around housing market risks facing banks, and is currently consulting on new guidance for sound risk management practices in housing lending.

And again in the section on Household and Business Finances:

The pick-up in household risk appetite that was evident six months ago appears to have continued, as has the associated willingness to take on some types of debt. Housing prices have been rising strongly in the larger cities. To some extent, these outcomes are to be expected given the low interest rate environment and the search for yield behaviour of investors more generally, both here and overseas. However, the composition of housing and mortgage markets is becoming unbalanced.

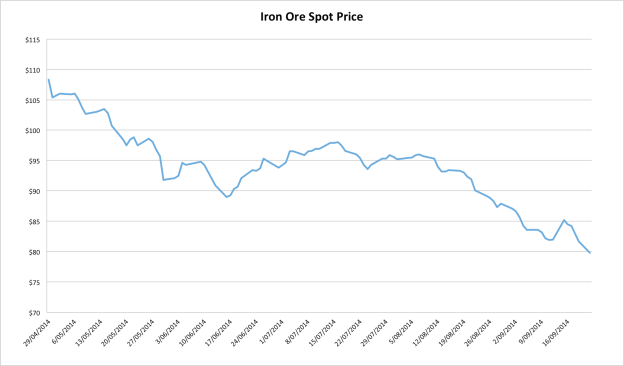

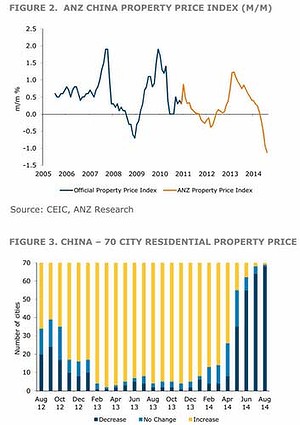

Nervous about housing and laying much of the blame at its own feet (low interest rates). As I’ve said a number times, the robust housing sector is the one area of the economy that argues for higher rates, whereas slumping commodity prices, the wind-down in mining investment and weak domestic demand generally all argue for lower.

A look through the Review’s charts helps elucidate the situation in housing.

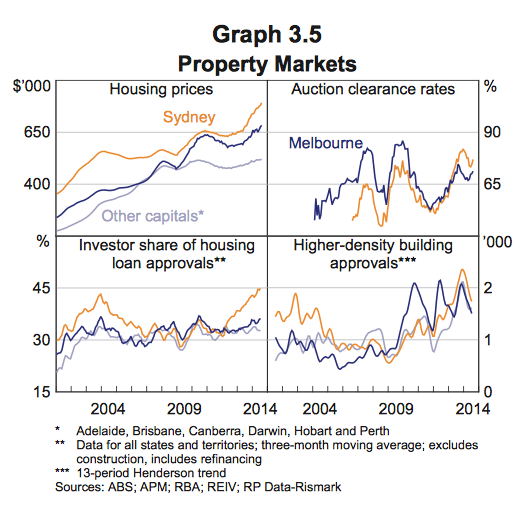

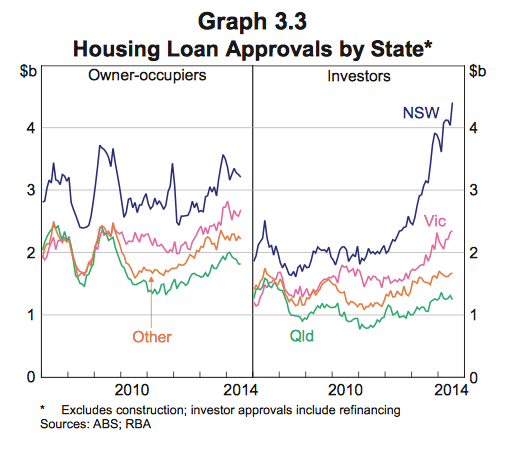

I have previously discussed the property investment frenzy which took hold in the early years of the millennium, and this is clearly visible in the above charts (note the investor share of housing loan approvals includes refinancing in that chart, my own chart did not). Indeed, by the standards of 2003-04, the current run-up in investor borrowings looks paltry. However, it must be remembered that we began from a much higher base in 2013. Moreover, the national figures mask the fact that the current boom has been centred on Melbourne and Sydney, with the latter easily accounting for the most fevered activity. This we can observe in both the pace of house price appreciation in Sydney (above) and the parabolic explosion in investor loan approvals (below).

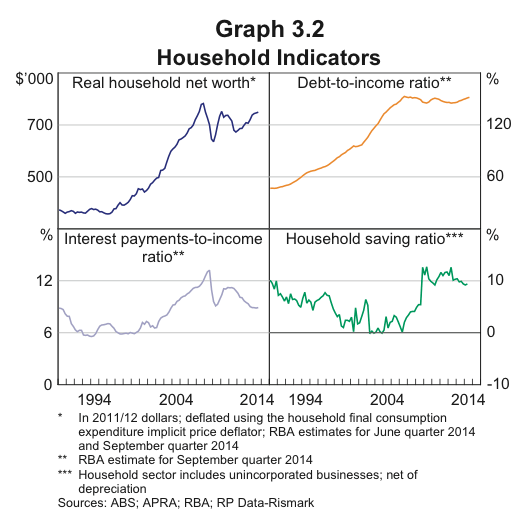

The RBA believes the primary threat this poses is to real macroeconomic conditions, rather than to the stability of the financial system (which would exacerbate the damage the macroeconomy, of course). For now, I think this is a fair assessment, since we haven’t seen the kind of deterioration in lending standards that usually characterises bubbles that go on to destabilise financial systems (though this is heavily dependent on how serious the terms of trade downturn gets). The adverse impact of falling prices on lenders occurs when loans repayments become impaired; house prices can fall without borrowers necessarily defaulting, provided they have sufficient net worth to weather the capital loss on property assets. Low net worth buyers are simply being priced out of the market, so the argument goes, and therefore we don’t need to worry about surging non-performing loans in the event of a property downturn.

Nevertheless, Australian households remain highly indebted, and the debt-to-income ratio is exposed to a shock to incomes arising from the falling terms of trade and resource-sector investment. So even if the banking system doesn’t suffer systemic instability, there is still scope for the housing market to hit consumer spending.

To my mind, the issue is that housing risks inflicting a wealth shock on Australian households at the same time that they experience an income shock due to the unwinding of the twin booms in the terms of trade and resource-sector investment. Households exhibit measurable propensities spend out of their current income, which is hardly surprising, but spending patterns also react to changes in wealth. By allowing house prices to appreciate as they have, policymakers added another unwanted risk to the economy as it enters the post-boom adjustment.

What to do?

If the housing boom was primarily a response to low interest rates, and if little else in the economy argues for higher rates aside from booming housing, then the RBA is plainly in a bind. The economy would be suffering grievously today if the RBA hadn’t reduced the cash rate over the period it did (late 2011 to late 2013), but it now has a disconcerting housing boom on its hands as a result.

As it turns out, this is a widespread dilemma which many developed economies have had to contend with in recent years. Largely due to structural changes in the global economy, over the past decade and a half, many developed economies have faced low inflation and weakening labour markets (especially amongst low-skilled workers). The popular prescription to this problem was to lower interest rates. As it turned out, lower interest rates exhibited a tendency to drive credit growth and asset prices higher, to a much greater extent than goods and services inflation. This was a challenge to orthodox thinking on economic policy.

A suite of policy tools have therefore been gaining popularity since the GFC as a way of addressing this conundrum. Known as macroprudential regulations, these tools are aimed at curtailing the speculative excesses that tend to appear when interest rates are low, thus avoiding the need to hike interest rates in environments that would otherwise not warrant them. The Economist has a useful primer on macroprudential policies.

The RBNZ introduced macpru policies last year, chiefly restrictions on high loan-to-valuation residential mortgages, and this seems to be having the desired effect. After vocal calls for the RBA to adopt (through APRA) a similar approach in tandem with its cuts to interest rates, we are finally seeing some receptiveness on the Bank’s part. I have highlighted the relevant comment from the Review, which strongly suggests regulators are preparing to introduce these policies.

Then, early this afternoon, we received virtual confirmation that the RBA will push ahead with macpru controls to address the investor segment of the property market. This is a most welcome development and sensible policy. Stevens is correct that there is little downside to experimenting with these policy options, which was always one of the foremost points of recommendation.

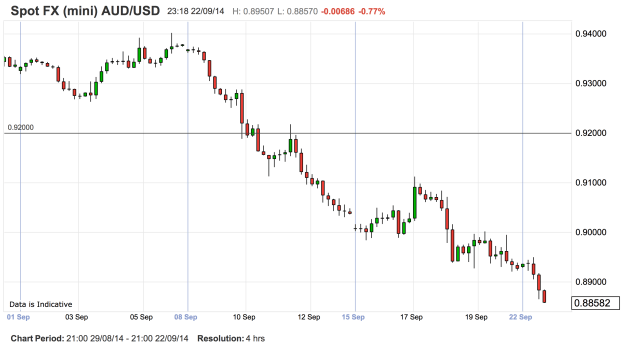

The AUDUSD was hammered on Stevens’ remarks; the FX market knows as well as I do that the investor property boom is the chief factor holding up interest rates!