The Australian cash rate is one of the focal points of this blog. In my first post on ‘Strayan rates, I wrote:

Picking the path for the RBA’s cash rate is a prime task for any would-be economic forecaster, as it’s both a key indicator of economic conditions as well as a critical determinant of them.

Whenever the RBA next adjusts the cash rate, it bears acknowledging that the 25bp move isn’t likely to be the critical determinant of economic conditions at that point in time. It will have an impact, but my focus has more to do with what the move will intimate about the state of the economy.

With this in mind, my first series on rates sought to sketch out a portrait of the Australian economy. My conclusion was that the evidence pointed to a greater probability that rates would fall with the next move, rather than rise.

Each month or so, beginning with this post, I’ll provide an overview, of varying detail, of the most important economic indicators for Australia, and update my view on interest rates accordingly.

Onya, Timmy!

Before I begin I want to mention the work of Tim Toohey, head of Macro Research for Australia and New Zealand at Goldman Sachs. I intentionally singled him out in that first post two months ago, as the loss of his rate cut call at the time left blanket agreement across institutional research teams in Australia that the next move in the cash rate would be up. (What better moment to dive in and swim against the tide, I thought!)

He abandoned this call with considerable reluctance, and last week he reiterated why that was the case:

A feature of our research over the past 18 months has been to break away from the guide posts that have served us well in obtaining a read on the future direction of economic activity over the past decade. Historically we had looked to easing financial conditions, rising confidence and rising wealth as important touchstones for a future acceleration in economic activity. These were indicators that had proved their worth over the prior 30 years. As such, our decision to adopt a far more cautious view than the consensus over the past two years was not born of the idea that these indicators were suddenly of less worth. They were born from the idea that there were other forces that were likely to be more powerful, namely the likely sharp decline of the terms of trade, the likely sharp decline in mining investment and a lack of economic incentives to drive a pickup in broader business investment, the likely persistent challenge of fiscal consolidation and an uncompetitive production base relative to Australia’s trading partners.

As will be clear to anyone who has read Strayanomics in any detail, this matches my own view of the economy with precision. (The most prominent voice advocating this view has long been David Llewellyn-Smith of Macrobusiness, to whom I owe much. Lately, Stephen Koukoulas has also joined the merry men, and is the only economist of 27 surveyed by Bloomberg who expects the next move to be a cut. For a longer-term perspective on why those of us calling rates lower are doing so at this time, see Ross Garnaut’s Dog Days, an immensely insightful book.)

Back to that first ‘Strayan rates post:

In a country like Australia, changes to interest rates tend to be quite effective in influencing economic conditions. Lower rates stoke borrowing, asset prices and consumption, giving way to higher rates, and vice versa. Why then are we drifting across a calm blue ocean of low interest rates?

Primarily due to the uneasy schism that has emerged in our economy. On the one hand we have the descent from what has almost certainly been the biggest terms of trade/investment boom in our nation’s history. On the other we have a raging house bubble boom. Which force prevails in this struggle will determine the short- to medium-term direction of interest rates.

As the rest of that series made clear, I have based my forecast for lower rates on the view that the terms of trade decline, the mining investment wind-down, lacklustre business investment ex-mining, the fiscal squeeze, and weak competitiveness would outweigh the impact of rising asset prices, speculative activity and consumption demand that have flowed from the last easing cycle. When Mr Toohey discarded his longstanding rate cut call in mid-August, he was conceding to the power of the latter.

Nevertheless, he has made a strong case for the ongoing possibility that rates could fall further, and his thesis is one that I think deserves attention.

Outline

The rough qualitative model I’ve been using essentially places the terms of trade and mining investment downturns, along with weak government finances and Australia’s poor competitiveness, into the structural basket. On the other hand, brisk gains in house prices, which have been driven increasingly by investor mortgage lending, and the boom in residential construction (especially apartments), I place in the cyclical basket, as they’re directly attributable to the last easing cycle. It’s a slightly clumsy oversimplification of terminology, but it serves its purpose.

Broadly speaking, structural forces argue for lower rates, whereas cyclical forces tentatively argue for higher. This, of course, is exactly the dynamic Tim Toohey and others have been emphasising.

Terms of Trade

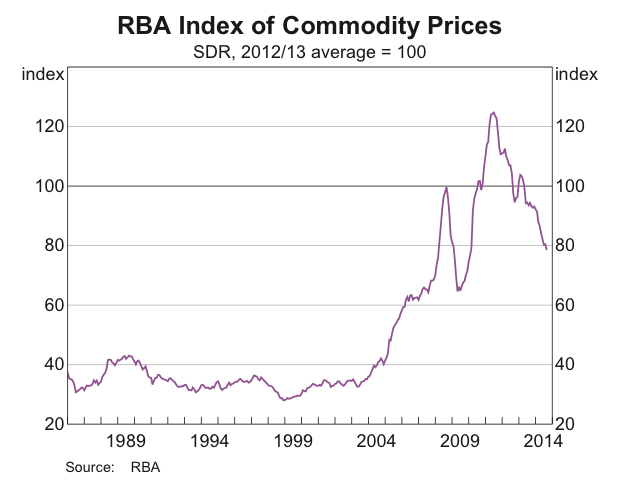

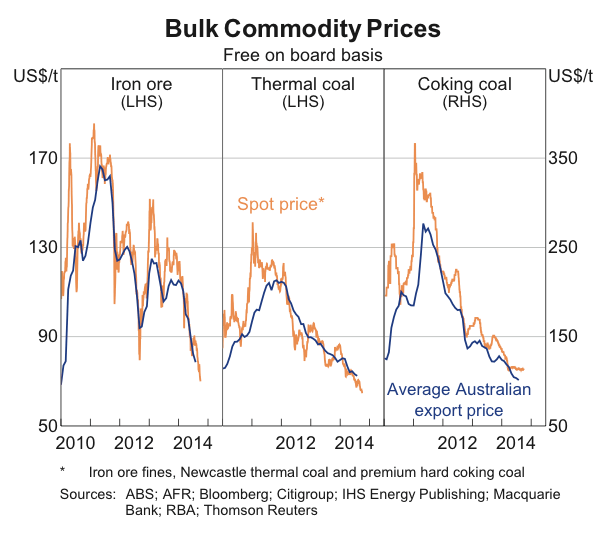

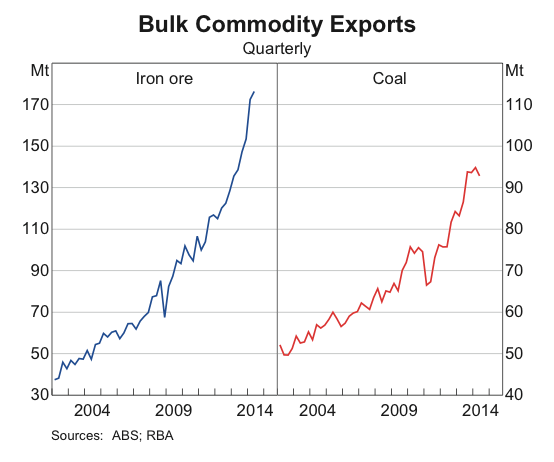

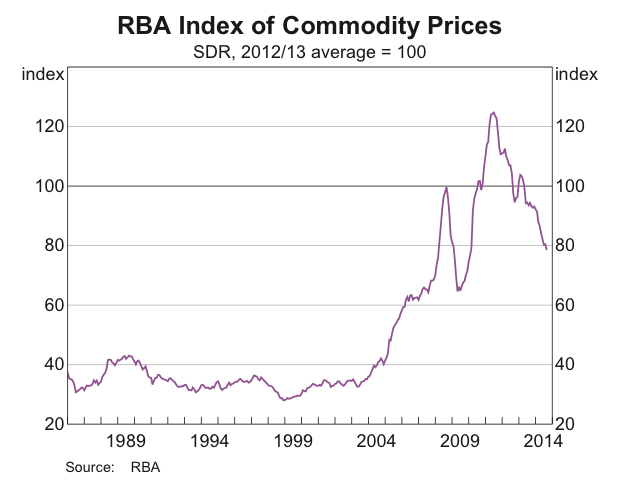

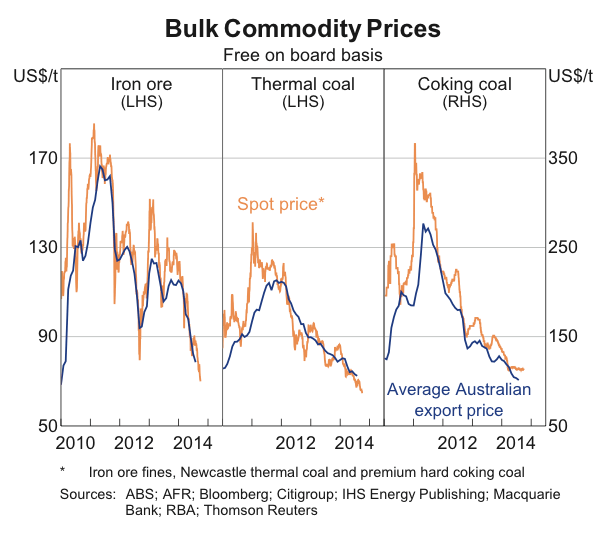

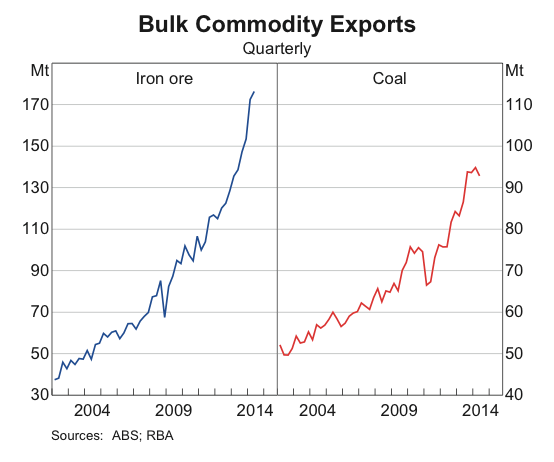

Commodity prices have seen further deterioration in the last couple of months. Iron ore and coal contribute approximately 35% of Australia’s export revenues. LNG contributes much less at present but its share is set to jump enormously over the next few years.

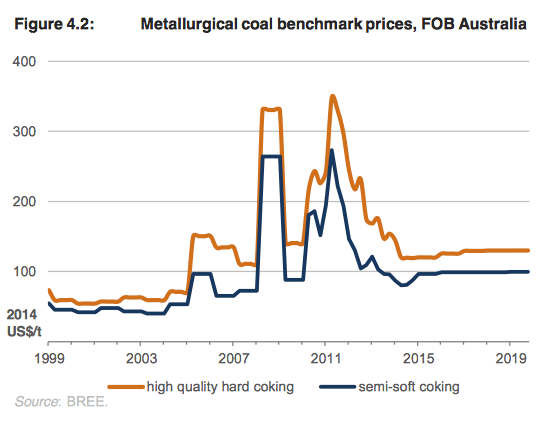

As reported in the Australian, there was some hope of a rebound in coking coal recently.

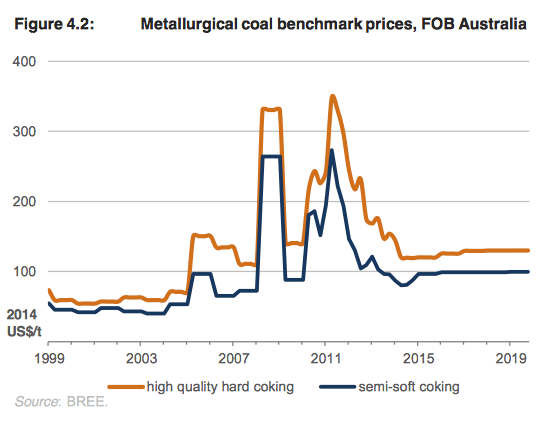

Like iron ore and thermal coal, prices for coking coal — Australia’s second-biggest mineral export earner — have been hard hit this year, falling by 24 per to $US113.50 a tonne on a spot basis.

But the call has gone out that prices have bottomed and are set to bounce back to between $US130 and $US150 a tonne in the near term, and $US170 a tonne in the longer term.

Unfortunately, this optimism was short-lived, from Bloomberg:

The quarterly benchmark price for metallurgical coal dropped to a six-year low, according to Doyle Trading Consultants LLC, amid a slowdown in Chinese demand for the steelmaking ingredient.

Australian coal producers and Japanese steel mills agreed to a fourth-quarter price of $119 a metric ton, down a dollar from the third quarter, Grand Junction, Colorado-based Doyle Trading said in a report yesterday.

Chinese imports in August were 39 percent lower than a year earlier, according to customs data, amid a glut of domestic steel. Iron ore demand is also suffering, with prices at a five-year low.

May I say, the idea that coking coal is going back to $170 is fanciful for the foreseeable future. Not even the BREE expects this, despite its unimpeachable record of overestimating future commodity prices.

Likewise, thermal coal offers little cause for cheer, squeezed by continued (though reduced) oversupply globally and the shale boom in the US (which has seen gas displace coal as a power source).

From the BREE:

Coal prices are forecast to remain subdued throughout the remainder of 2014 in response to weaker import demand from China and a continued abundance of supply. At lower spot prices many producers are unprofitable, which is expected to support further cost-cutting measures and signals the risk of more mine closures or production curtailments over the remainder of the year.

While coal consumption is forecast to remain robust in 2015, particularly in the Asia-Pacific, the global supply overhang is expected to persist and contribute to continued softness in prices. Contract prices for JFY 2015 are forecast to decline by 6 per cent to settle at US$77 a tonne. From 2016, the market balance is expected to tighten as import demand continues to increase and lower prices during 2014–2015 reduce investment in new capacity and force less competitive operations to close. The contract price is projected to rise to US$86 a tonne (in 2014 dollar terms) by 2019.

Despite tougher times, coal isn’t going anywhere. Aggressive expansion plans are being tempered, but the industry will continue to make a significant contribution to Australia’s economic output and export earnings. Nevertheless, the days of coal serving up windfall profits and tax revenues are past.

As you can see from the chart below, Australia’s exports of LNG are set to skyrocket over the next couple of years, making Australia the world’s largest supplier.

This will improve Australia’s trade balance and therefore boost headline GDP, however we’re unlikely to see the kind of boom in corporate profits that characterised the iron ore and (to a lesser degree) coal booms over the past decade. I have written about LNG here. Since the impact on domestic demand will be minor once the surge in exports begins, and may even be negative as local gas price leap and construction workers are laid off, LNG offers little in the way of upward pressure on Australian interest rates.

With the glory days of coal long since past, the burden shifted to iron ore to keep the party alive. Sadly, as you can see from the RBA’s chart, iron ore has had a particularly rough ride in 2014. Here is my own year-to-date chart:

This year’s decline is directly attributable to soaring supply from major producers, especially Australia.

Rising volumes are offsetting some of the squeeze on profits margins, but not enough to prevent a big hit to the economy if prices remain at or near current levels.

Recently I noted that the worst may well have passed for the iron ore miners in 2014. Spot found legs for a solid bounce after that, however as you can see it didn’t manage to hold its gains. Still, buying returned at the end of last week around the $80 level, and it looks unlikely we’ll see falls much below this for the remainder of the year, owing to much improved profitability amongst Chinese steel mills, a thawing of credit conditions in China and some degree of seasonal inventory restock into the year’s end. However, without a fundamental shift in Chinese policy settings, the bounce will be short and soft relative to past years. And with no sign of a let up in the pace of supply expansions from the majors, further declines in iron ore next year are virtually baked in.

China

It should be no secret by now that China faces an immediate choice between slower, sustainable growth that is much more biased towards domestic consumption in place of investment, or faster growth that’s increasingly unstable and ultimately unsustainable. The government is more than aware of this trade-off, and has largely opted to curtail the excesses of previous years (without being too aggressive). Should the government’s resolve waver in the face of a more serious downturn, then risks would increase of a ‘big bang’ stimulus that could temporarily elevate demand for raw materials and most likely provide a sufficient boost to Australia to see rates rise, also temporarily, as cyclical influences take precedence.

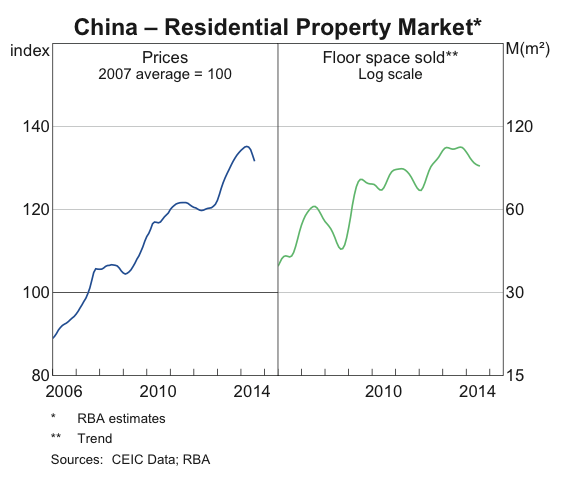

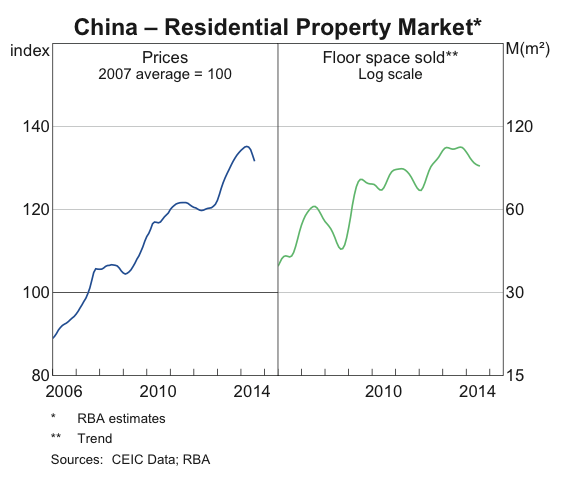

China has witnessed a noticeable slowdown in the property sector this year, which has weighed on growth.

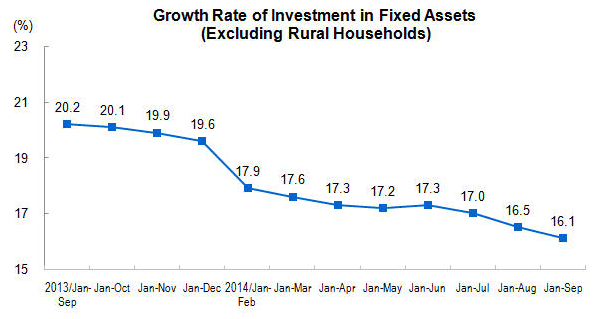

Along with the usual monthly data indictors, we received China’s national account data this week. As you can see, the growth rate of real estate investment continues to slide.

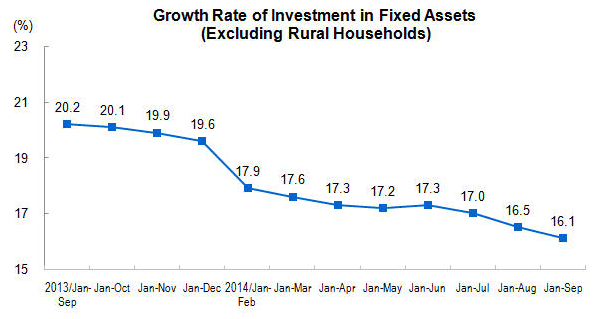

This is dragging down fixed asset investment generally, which is by far the most important form of spending for Australia’s economy.

I only have data going back a decade, so all I can say is that this is the slowest pace over the period I can see. But I would be very surprised if this were not the slowest since the Asian Financial Crisis or earlier.

The property-related slowdown has been sharp, and so far as I can discern, only a jump in net exports has cushioned the blow to GDP growth (cynical observers may be less charitable). For a large part the slowdown is the result of policy restrictions on mortgage lending this year, among other measures. However, unlike the previous cooling in 2012, the property market now appears to be structurally oversupplied (and even more overvalued). Looser credit conditions could certainly mitigate the severity of price declines, but it would require a complete abandonment of credit rationalisation to reignite the boom, which the government has long been reluctant to do.

Thus it was to much fanfare that the government eased restrictions on mortgages late last month. This is apparently already lifting activity in tier 1 cities. Credit growth remained subdued in September, and this is going to be the key indicator going forward determining whether the looser policy stance translates to a meaningful resumption of price gains and investment activity. I don’t think we’ll see this, but I wouldn’t be surprised to see the slowdown moderate, or mild gains in prices over the next 6 months. Nevertheless, I’m highly sceptical that this moderation, if it does manifest, will be enough to mop up excess steel supply, and even less so excess iron ore, implying more pain for the latter next year.

It appears that China’s rebalancing (which is a polite way of saying ‘slowing’) is continuing, albeit with the government easing its foot off the break a little. I still do not see a resumption in the kind of frenzied building that delivered Australia’s commodity bonanza and was extrapolated far out to justify surging investment in capacity (and still is). With another wall of iron ore supply careering towards markets next year, policy shifts from China have not yet been substantive enough to change my view on Australian interest rates.

Investment

Not much to report here since my post on engineering construction work a couple of weeks ago. The outlook remains soft as LNG mega-projects wind down.

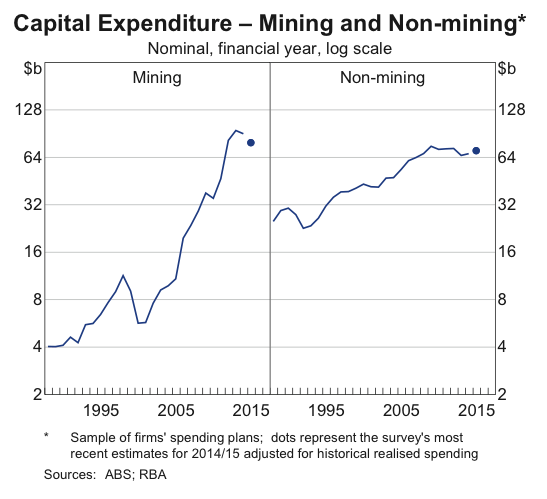

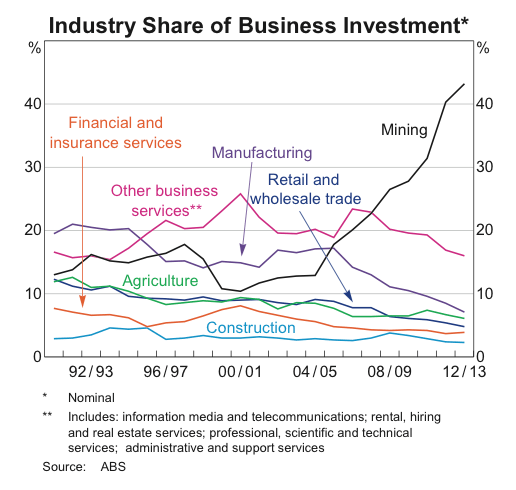

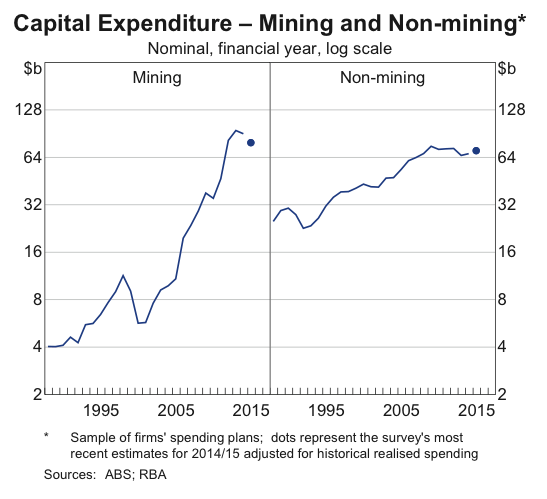

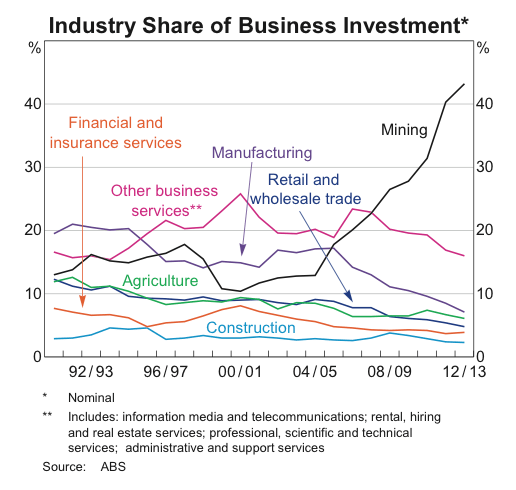

A couple of charts from the RBA help paint the picture.

Mining investment is set to decline sharply over the next two years, and non-mining business investment will need to be revived to mitigate this. To do so, the AUD will almost certainly need to come down markedly. In the absence of this, business investment is going to be a big drag on the economy and will argue in favour of lower rates.

Public Finances

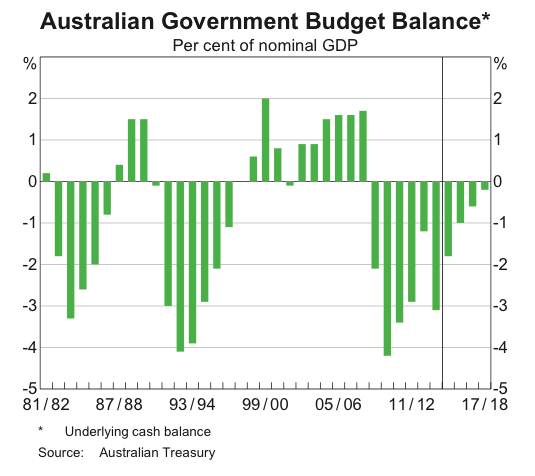

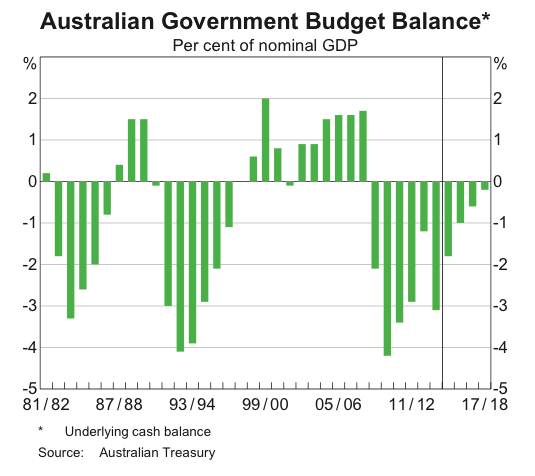

The federal government handed down a tough budget in May in a bid shore up public finances. Partly owing to this effort, the deficit is expected to decline over the next few years.

It is very hard to see this happening with iron ore where it is. The AUD is lower than was forecast, but this has not been enough to offset the larger-than-expected decline in the terms of trade. In addition, the government has had great difficulty getting its savings measures through the Senate. Do not be surprised if the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook (MYEFO) in December shows a marked deterioration compared with what the government had intended.

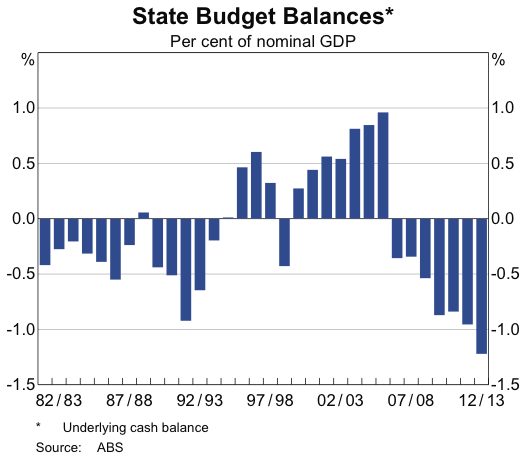

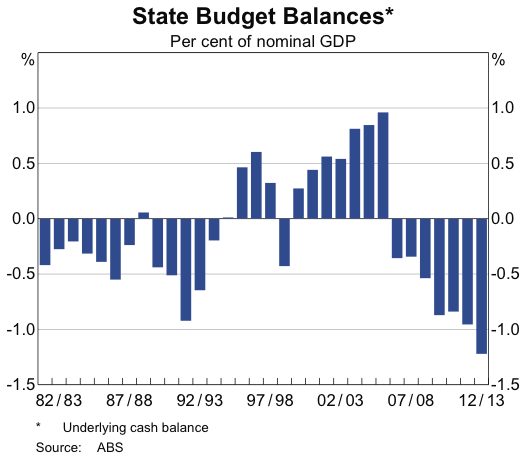

State balance sheets are also under pressure, and it’s only been the property booms in Sydney and Melbourne that have prevented much worse outcomes in NSW and Victoria this year. By their nature, the support from these booms will prove transitory.

The pressure on public balance sheets will in turn keep the pressure on governments (both state and federal) to search for further savings, which households will not like. The outlook for the Australia’s fiscal settings therefore offers scope for further monetary easing.

Housing

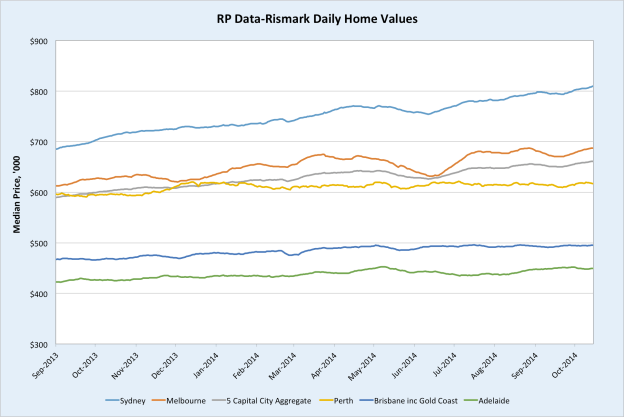

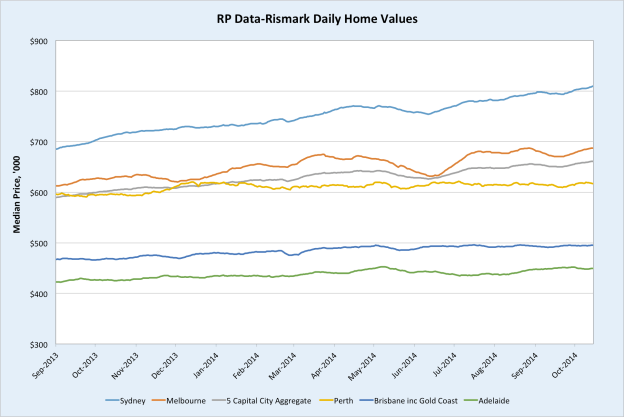

The housing sector remains robust, with no let up in prices over the past month.

And for a longer term perspective:

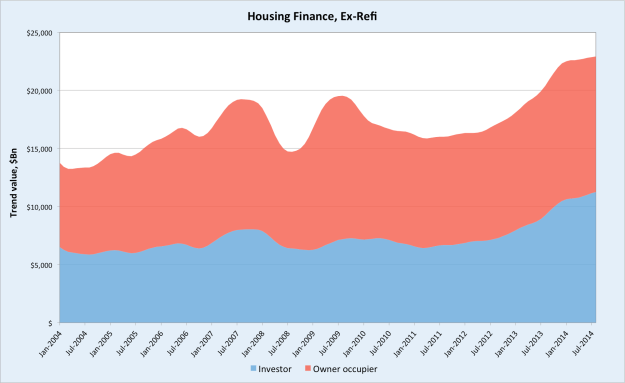

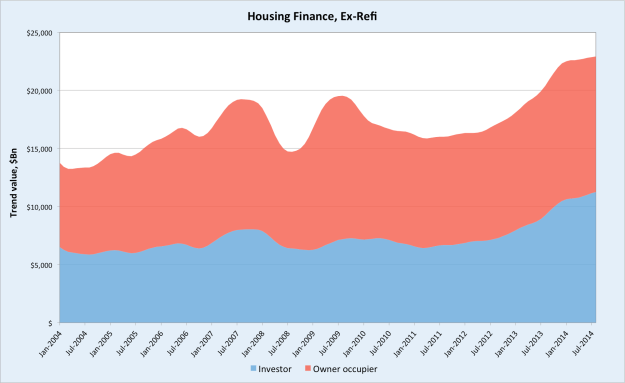

Naturally, this has been driven by surge in mortgage lending over the past 2-3 years.

Notably, however, owner occupier lending has clearly flattened out this year, while remaining at an elevated level (the share going to first home buyers has collapsed).

This has meant local investors and, to a degree we can’t fully ascertain, foreign ones, have become increasingly dominant in the Australian housing market, especially in Sydney and Melbourne.

With strong prices in the capitals, dwelling construction is booming, at least relative to recent history. (It is true that Australia has long underinvested in housing, though not the extent that it can fully explain recent price gains.)

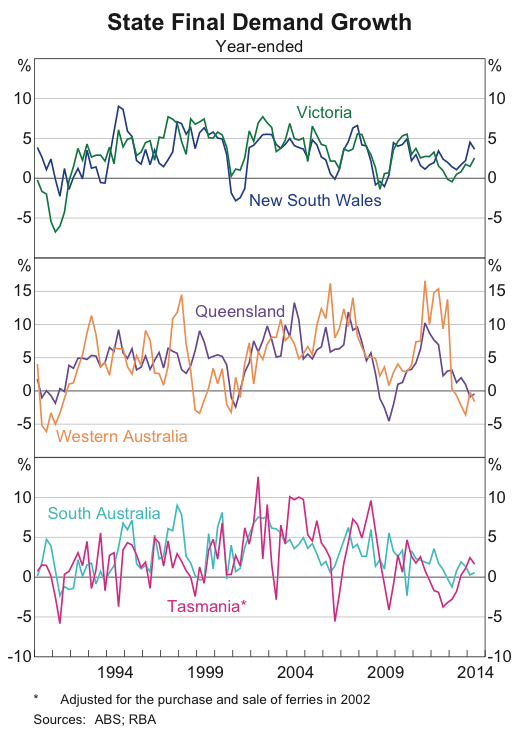

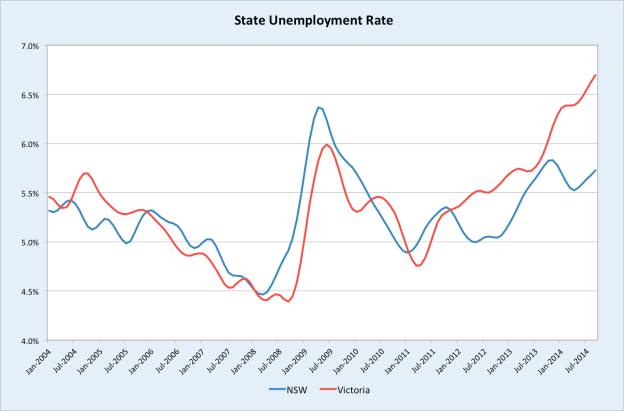

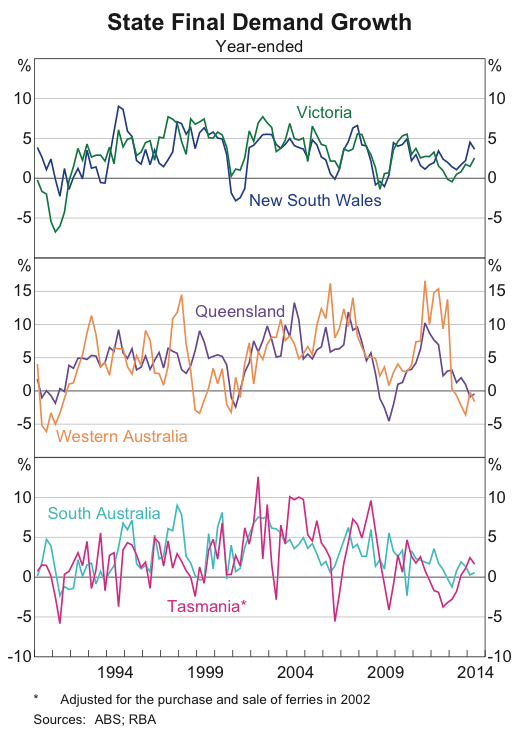

One result of this building boom has been a shift in the relative economic performance of the states. Reversing the pattern of previous years, state final demand has been contracting in Queensland and WA, while being stronger in NSW and Victoria.

This excludes exports, so it’s misleading to say QLD and WA are in recession. However, foreign purchases of a state’s export commodities don’t necessarily provide much in the way of direct support for local jobs; it was monster profits and hurried investment that had a big impact on local economic conditions. And this is a reality that will be felt more acutely in the coming years as profits continue to fade and investment winds down.

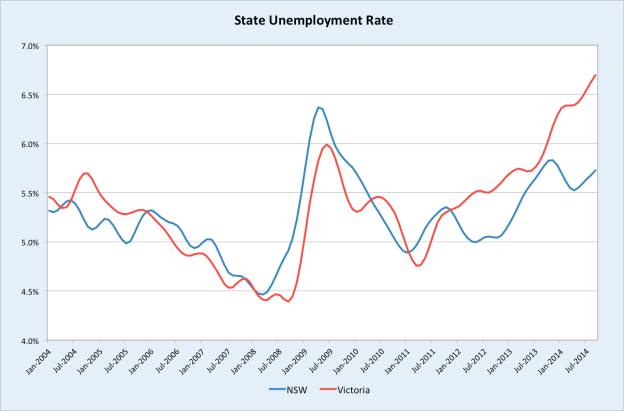

In spite of healthy growth in demand in NSW and reasonable growth in Victoria, unemployment rates remain elevated, with Victoria faring the worse of the two.

Nationally, rents are now growing roughly in line with the CPI, while house prices are up around four times that. Rental yields have plunged as a result and will of course continue to do so if prices keep rising. It is often argued that high house prices in Australia can be explained by tight supply. Supply has not been as responsive as it could be, but if it really were a central reason for elevated house prices, then renters should be getting squeezed harder than they are. Since it’s prices that are soaring, but not rents, we can conclude that the demand side of the market is the primary driver of house prices.

So we have a hot housing market that is being propelled by investors seeking returns in the form of capital gains, since income produced from these assets is paltry. As more supply hits the market, growth in rents will remain subdued and may even fall. Low income generation can be justified when interest rates fall significantly, since this reduces the cash outflow from the investment. As prices rise, larger mortgages are required to speculate on houses, weakening the economic case for housing investment. Thus there is a limit to how far a housing boom will run on lower interest rates alone (though what that limit is precisely is a matter for the behaviourists). Indeed, recent consumer surveys have indicated that expectations for house price growth have well and truly rolled over.

In addition, we have the RBA signalling it will implement some form of macroprudential regulation by the end of the year, in a bid to cool investor activity in the housing market. Whether or not this has a significant impact in the absence of rate hikes remains to be seen. But I would expect it to hurt at the margin at the very least.

I can see the boom in house prices continuing for perhaps another 6-9 months before running out of puff. If macpru bites hard, then it may wind down earlier. Exactly when this latest investor frenzy for housing cools is immaterial, what matters for our purposes is that this boom is not translating into labour market tightness or inflationary pressures. On the contrary, the boom is barely holding the unemployment rate where it is. Hiking interest rates to deflate the housing boom would therefore necessitate lower rates in quick succession. For these reasons, I continue to judge that the RBA will not feel compelled to hike rates to quell strength in the housing market, which is likely approaching its denouement anyway.

Consumers

See here for a more detailed treatment of consumer spending.

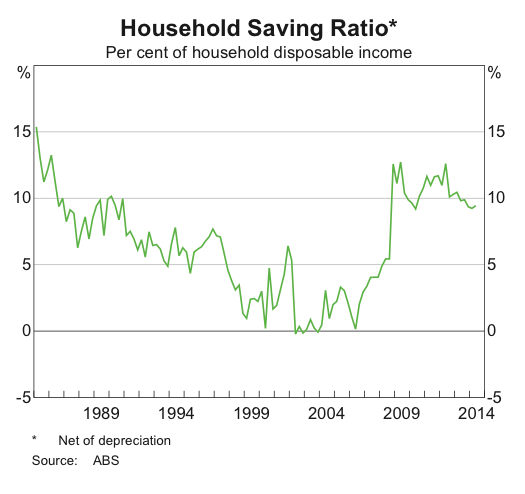

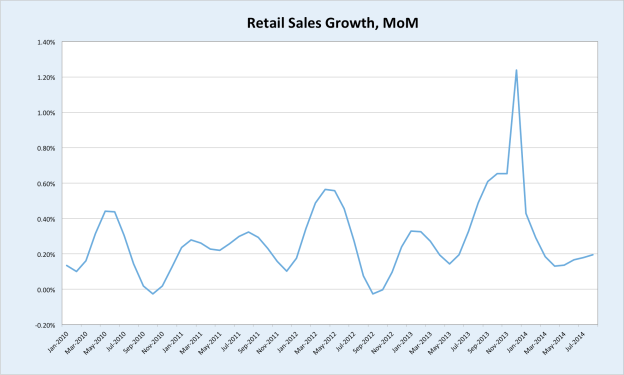

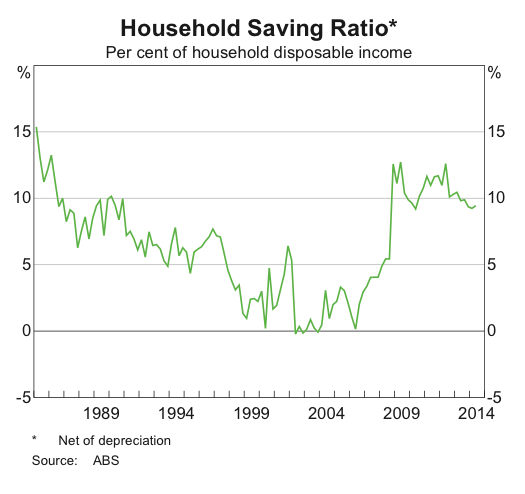

A large part of the why the housing boom has not had the wider economic impact one might have expected is that households have been reluctant to respond to higher net worth in the usual manner of saving less and spending more.

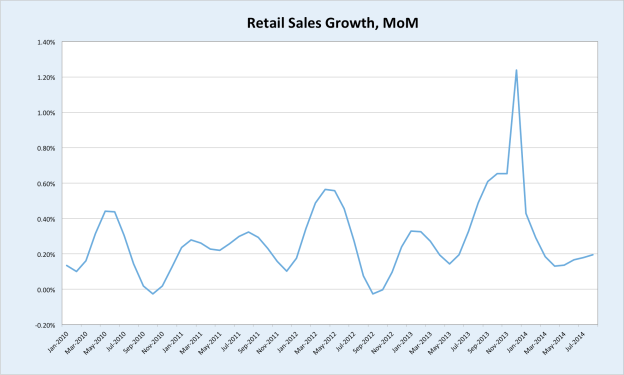

After a jump into Christmas, retail sales growth has been tepid this year; not what you would expect given the ongoing improvement in household wealth.

I cannot be sure exactly why Australian households have altered their behaviour in this way. Watching financial meltdowns and long, deep recessions across much of the developed world has probably endowed us with a greater degree of cautiousness towards gains in paper wealth. The budget undoubtedly damaged sentiment, and the travails of commodity prices will be hurting as well, especially in WA.

Whatever the cause, consumers have chosen to remain stubbornly parsimonious in the face of rising wealth. Until they throw caution to the wind, there is little in the outlook for consumer spending to recommend higher interest rates.

Inflation

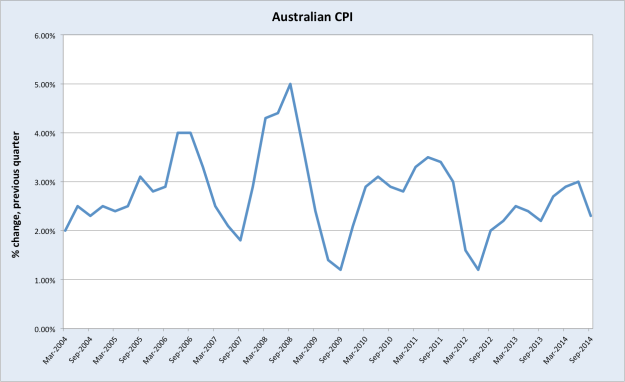

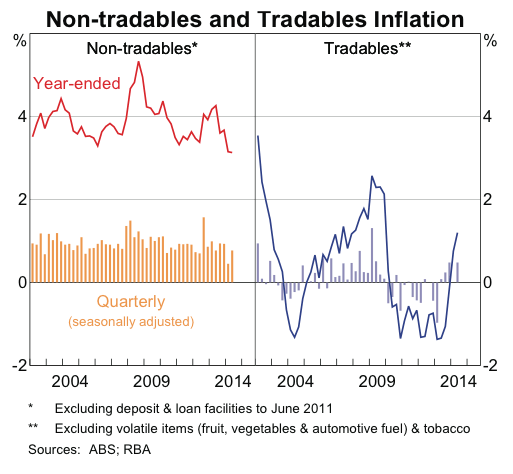

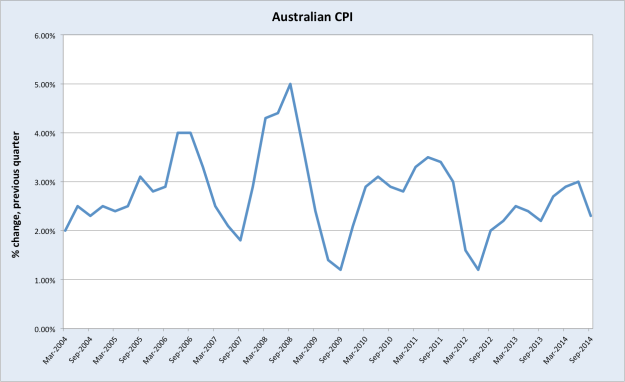

I’ve paid relatively little attention to inflation in Australia in my posts on interest rates, which may seem strange given the primacy of price stability in the RBA’s mandate. The reason I haven’t looked at inflation much is because I don’t consider there to be any serious risk of it posing a problem for the RBA.

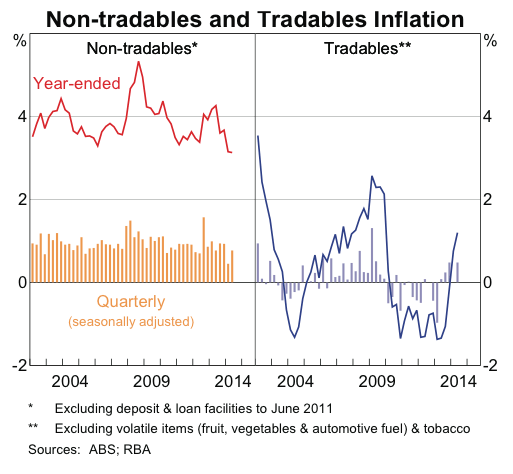

There was some hand-wringing this year among more excitable observers as the CPI bumped up against the RBA’s ceiling rate of 3% (the RBA seeks to contain inflation at 2-3%). For the past year I have steadfastly maintained that this was a temporary occurrence resulting from the sharp decline in the Australian dollar last year (which raised the price of imports) and the introduction of the carbon tax. The effect of ‘tradables’ inflation on the CPI, from rising import prices, was especially pronounced.

Rising tradables inflation from one-off adjustments in the value of the AUD is not problematic, in fact it is wholly desirable at this time. As I have discussed previously, one of the central economic challenges for Australia is our elevated real exchange rate, which translates to weak international competitiveness and therefore low business investment in trade-exposed sectors outside resources. The least painful way to devalue your real exchange rate is to reduce the value of your nominal exchange rate (the value of your currency against other currencies) and not offset this with higher wages. Wage growth is very low today and the AUD is falling against other major currencies, so progress is being made. By its very definition, a lower nominal exchange rate implies higher import prices; this is what it means to improve Australia’s competitiveness. For this reason, tradables inflation is desirable so long as the depreciation of the currency does not spiral out of control (and there is very little prospect of that today).

Australian Dollar

This need to improve Australia’s competitiveness was why I highlighted the Australian dollar as an additional and important consideration in Part 5 of my initial series on rates. A significant drop in the AUD would alleviate many of the structural weights hanging around the neck of the economy. It would improve the profitability of exporters, and so cushion the blow to public finances from falling commodity prices. If large and persistent (and not offset by higher nominal wages), a fall in the AUD would in time revive weak business investment outside the resource sector. All this ought to support employment. While a lower currency is not a silver bullet for all Australia’s challenges (it would make our over-inflated house prices even harder to justify, for instance), in reducing the drag on the economy from various structural weaknesses, it would reduce the likelihood of rate cuts.

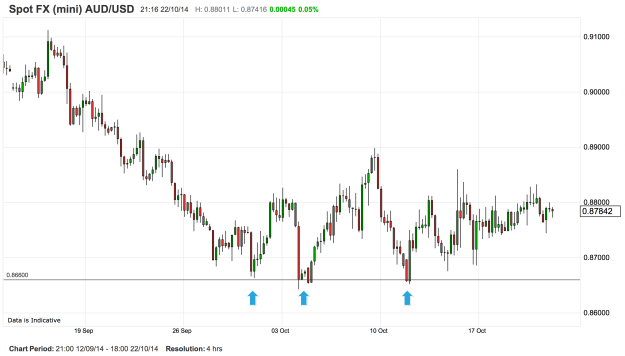

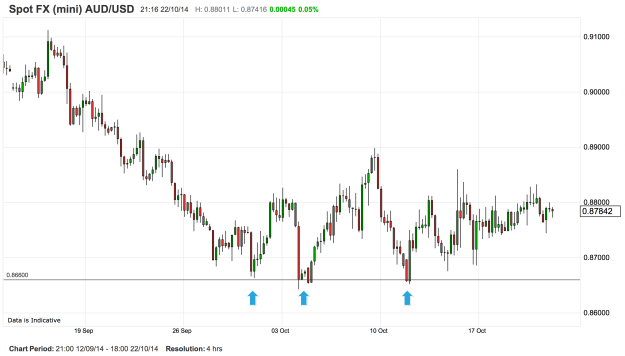

As you can see on the chart below, the AUDUSD had tumbled below support at .9200 and was trading around .8900 at the time of my last Strayan rates post. Since then, it has fallen further but stalled once it hit strong support at the previous low of .8660, set in January this year.

The bears have mounted a concerted effort to break this support on no less than three occasions since the end of September, and failed each time.

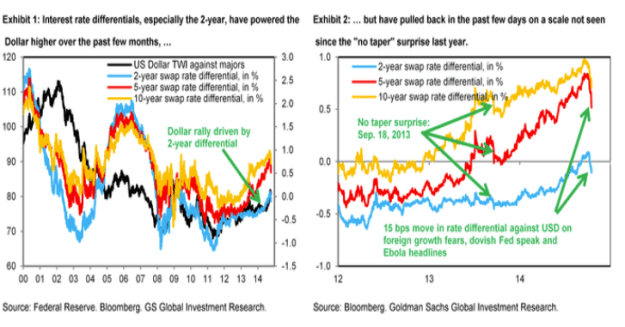

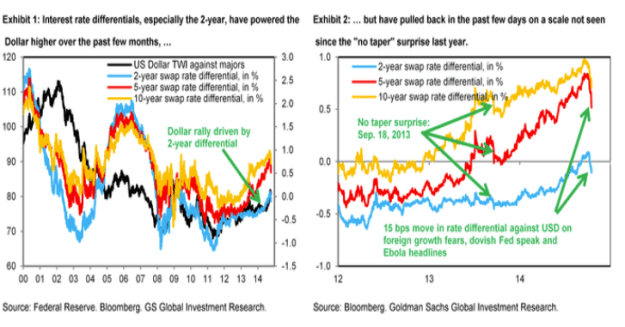

Plainly, this support is going to be harder to break than it appeared to me a couple of weeks ago. The picture is has grown a murkier due to the sharp decline in US interest rates last week. Lower interest rates reduce the attractiveness of holding a currency, and so tend to see its value decline. (charts courtesy of ForexLive).

Bonds have settled down after the craziness of last week, but all eyes are now on US inflation data later tonight. Should those data undershoot expectations, and I would say that is a distinct possibility, then US yields would likely come under further pressure, which would of course favour the AUD.

As I argued in my last rates post, I would be looking for the AUDUSD to head towards .8000 before concluding that the case for a rate cut had significantly weakened. Much depends on US data, and at the risk of impeccably bad timing with the US CPI just around the corner, I’ll say that .8660 looks safe for now.

Conclusion

Evidently, the cyclical factors I highlighted at the beginning of this post are under-delivering relative to their historical performance. The most energetic phase of the housing boom has been and gone, without inducing a sustained spending response from households. This has meant that the impact on labour markets has been insufficient to reverse the uptrend in the national unemployment rate. Inflation is benign. China continues to offer a window of possibility that maybe the government will ride to the rescue again, but circumstances have not changed in the Middle Kingdom enough to alter my view that the structural weaknesses bearing down on the Australian economy will lead the RBA to cut rates the next time it adjusts the cash rate.

For now I’m going with Q2 2015.

Data and charts sourced from the RBA’s monthly chart pack, the Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics’ (BREE) latest quarterly report, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, China’s National Bureau of Statistics, and IGMarkets.